This article first appeared in our winter ’19 issue of MyGreenPod Magazine, The Love Revolution, distributed with the Guardian on 22 February 2018. Click here to subscribe to our digital edition and get each issue delivered straight to your inbox

At the check-in area at Kilimanjaro airport, the airline desks are book-ended by two bold images: giraffes stoop on wobbly legs to drink from a lake, and a group of Maasai women smile from beneath a tree.

Someone, somewhere, calculated that the Maasai are one of Tanzania’s best adverts – and one of the most valuable memories for tourists to take home. Just like the wild animals that roam the various national parks, this semi-nomadic tribe is a huge draw for tourists who spend money on food, drink, accommodation and activities in Tanzania. Maasai-style jewellery and art is also sold at the airport and at roadside markets, for sums far higher than the Maasai would ever ask.

The giraffes won’t have received much by way of thanks or money for their modelling stint – and it’s unlikely the Maasai did, either. Their cultural property keeps businesses alive, but under normal circumstances their communities don’t see a penny of the profit. Worse, pressures on the Maasai’s pastoral lifestyle increase every year. While once the greatest threat came from neighbouring tribes ready to go to war over fertile territory, today the growth of business and tourism pose equal threats. The richest land is being fenced off for conservation projects and national parks that can command a gate fee, while suburban areas are being turned over for development.

Tanzania’s average annual industrial growth rate over the last five years has been 8%, contributing to 25% of the country’s GDP. In order to become a semi-industrialised country, manufacturing must contribute a minimum of 40% of GDP by 2025, and Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) are expected to provide the capital.

The Maasai way of life

While some of Tanzania’s tribes have adapted their lifestyles to accommodate new challenges, the Maasai have stayed fiercely true to their culture. They live from their cattle, consuming only milk, blood and meat – occasionally with rice. Maasai boys spend the daylight hours herding their precious stock from one grazing patch to the next, ensuring their animals get maximum nutrition from the land available.

As the cattle graze, the soil’s trampled and broken up beneath their hooves and seeds are dispersed, helping to improve the fertility of the land. The Maasai move their cattle expertly across the ground available to them; as the best pastures and water sources become increasingly privatised, fiercer grow criticisms that the Maasai scar a trail of barren dust across the limited and often already arid land.

The women continue to collect water, despite being forced, in some cases, to travel over eight hours – in blazing heat – because their villages can’t be situated closer to a natural water source without spilling onto new belts of private property.

The children who are old enough work with the cattle or help their mothers to collect water and fire wood. Those who aren’t stay at home and wait for their mothers to return. This means that in some cases the children can be left for most of the day without food or anyone to change their clothes if they don’t get to their wild loo in time.

The Maasai keep cows and goats for milk, meat and blood, and use donkeys – ‘Maasai Land Rovers’ – for heavy loads. They don’t eat any fruit or vegetables; their way of life makes farming almost impossible, and while their right to live on the land is recognised, their right to own it isn’t. The possibility of being moved on by authorities means it’s not logical to invest time or already sparse money or resources on a harvest that might very well fail anyway. The Maasai who do grow their own fruit or vegetables sell their produce at the market to raise funds for more cattle.

Living with the Maasai

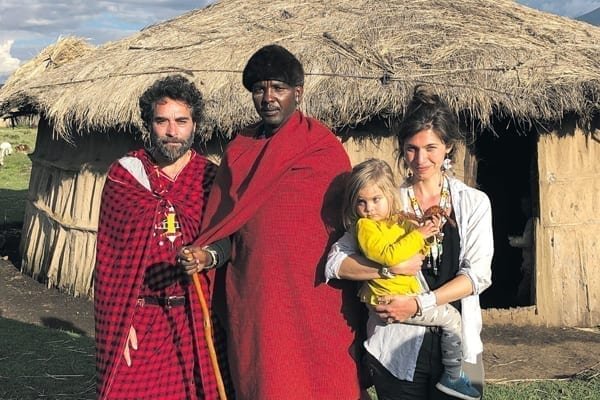

We experienced the Maasai way of life in January, when we went on a New Year trip with Visit Natives. This travel company was established as a way to ensure the Maasai benefit from the global desire to see and experience their way of life. Maasai communities receive a percentage of the money paid for the trip – Visit Natives makes very little profit – which supports immediate needs such as extra cattle and longer term projects, such as water butts for villages.

In exchange, we were able to live with the Maasai for six days; we slept in a tent inside the boma – a small collection of Maasai homes and animal pens – and deep in the bush to learn how their warriors are trained. We walked in their footsteps and tried to forge some sense of a connection with their ancient wisdom, which is deeply connected to nature. In translated conversations we learnt about their views, challenges, lifestyle, beliefs and needs.

Going native

We arrived at Kilimanjaro airport on 30 December, and half-heartedly scanned the names on the boards of safari-clad tour operators. Our Visit Natives contact, a Finnish lady called Anniina, had told us we wouldn’t be able to miss our hosts, who would be in full Maasai warrior getup. Before long a 4×4 pulled in to the car park and out jumped three men – unmistakably Maasai in their blazing red shukas and traditional jewellery. They were accompanied by Anniina, who had fallen in love with the Maasai way of life 14 years earlier.

Anniina’s story is important because it says a lot about Visit Natives and why she founded it. Fascinated by people and cultures, Anniina chose to study Anthropology, then switched her course to African Studies to satisfy a calling she had felt since childhood. As part of her course Anniina travelled to Tanzania to support women’s aid projects in the country, but quickly grew frustrated by the lack of work available and a sense she was unable to effect real change.

Anniina became known to the Maasai, and a local Maasai NGO invited her to live with them. Anniina leapt at the opportunity and, over the next two years, fully embraced Maasai culture. She became fluent in their language – Maa – as well as Swahili, and took part in ceremonies and rituals that had previously remained closed to outsiders. Anniina contracted malaria, typhoid fever and came close to death at least once, but she stayed until her visa expired and she was forced to return to Finland.

Anniina acquired an unrivalled understanding of the challenges the Maasai faced and wanted to find a way to support the community that had become her second family. She set up Visit Natives to provide a true, authentic experience of the Maasai way of life, for tourists who want to reconnect with nature and ancient wisdom.

The money from trips is distributed evenly among Maasai villages in the area so all families and communities benefit from a cash injection, irrespective of whether they are hosting the visitors directly.

Anniina and three Maasai warriors – Olopiro, (meaning ‘Wet Season’), Saitoti (‘Big Family’), Sumulek and Isaac, a Maasai chef – travelled everywhere with us, and soon became great friends. Maasai music, which blared from the Land Rover’s sound system the moment the engine started up, became the theme tune to our road trips, which took us through Arusha to Ngorongoro Conservation Area and back again.

Inside the Maasai boma

We stayed in a boma in Ololelai, Olopiro’s village, inside the Ngorongoro Conservation Area. We had our own tent but everyone else slept in houses – round structures made from cow dung, with one central room for cooking plus two or more separate bedrooms on raised mud floors. There is no toilet – though ‘authorities from the city’ have recently insisted on digging holes in the ground, which we never saw the Maasai use. They were full of flies and posed a far less appealing option than finding a bush a good distance away.

There were no windows inside the houses and, like most other Maasai villages, there was no electricity (not to mention wifi or phone signal). The only light came from a small door and the fire when it was lit for cooking. Unpolluted by artificial light, the Maasai’s eyesight seemed superhuman; each time we entered a house our eyes took several minutes to adjust in the darkness, and even then we needed to suspend a torch from the roof to make out faces and objects deeper inside the home.

Night vision is vital for protecting family and valuable livestock from wild animal attacks; armed with no more than a traditional spear, Maasai warriors keep watch over their village at night. The cows, goats and donkeys are herded into circular pens when the sun goes down, so they spend the night in relative safety. The animals provided the soundscape for our nights – bleating and changing position, melodic bells ringing from collars with every movement. It was a hypnotic and soothing way to fall asleep, in a spot beautifully distant from lights, cars and emails.

Bush camp

We weren’t aware of any visiting wildlife until we camped out in the bush to witness an Olpul, a ritual that sees Maasai warriors head out to the wilderness to build their strength.

A short drive from the village across open scrubland, the spot used for the Olpul could well be the most romantic place on Earth. From our spot high in the Ngorongoro bush we could just make out the Serengeti, the endless plains. They cover 14,800km2 of incredibly beautiful landscape that can be rich and fertile or a dry wilderness, depending on the season. For this reason animals have to migrate to follow the rains and find green pastures to graze. No photograph or words could do justice to the sublime landscape at the door of our tent – and we and the Maasai had the view all to ourselves.

Play Video about This Rock Might Just Save The World

Play Video about This Rock Might Just Save The World Play Video about Play 2 hours of rock

Play Video about Play 2 hours of rock Play Video about Play 2 hours of brook

Play Video about Play 2 hours of brook Play Video about Play 2 hours of sheep

Play Video about Play 2 hours of sheep